In the border area of Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zambia is Africa’s largest nature reserve. Ecotourism is designed to curb poaching in the region and provide locals with new sources of income.

“I’m wondering where the lions are!” Bruce Cockburn’s country voice whistles from the car radio. Tired, Paul Funston casts a glance over to the passenger seat, to Lisa Blanken, who wants to cheer him up with her playlist. For two days he has rocked his jeep at 40 degrees on sandy tracks, has heard how the thorn bushes scratched the paint. Has wiped the sweat, with which he searches the savannah for traces of lions, elephants, giraffes.

Now, the man from the Big Cat Protection Association Pathera and the wife of the Society for International Cooperation listen to the melancholy Buce Cockburn and wonder how the singer, where the lions are. Tired are they, done. Yes, they saw a lion’s trail, two, three palm-sized paws in the sand. A herd of buffaloes and zebras. They chased after a rare night-swallow at night and heard the yelling of a hyena .

And, yes, they are sure that this area of southern Angola could be a paradise for animals. But whether their trip is successful, whether the Luengue-Luiana sanctuary in the former civil war country can ever fulfill the hopes of international researchers, development workers and tourism managers – that’s far from certain.

Conflicts between humans and animals in the Kaza region

The Luengue-Luiana National Park is one of 36 national parks and reserves, connected by corridors to a more than 520,000 square kilometer nature reserve. From Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zambia to Zimbabwe, the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (Kaza) is the largest protected area in Africa.

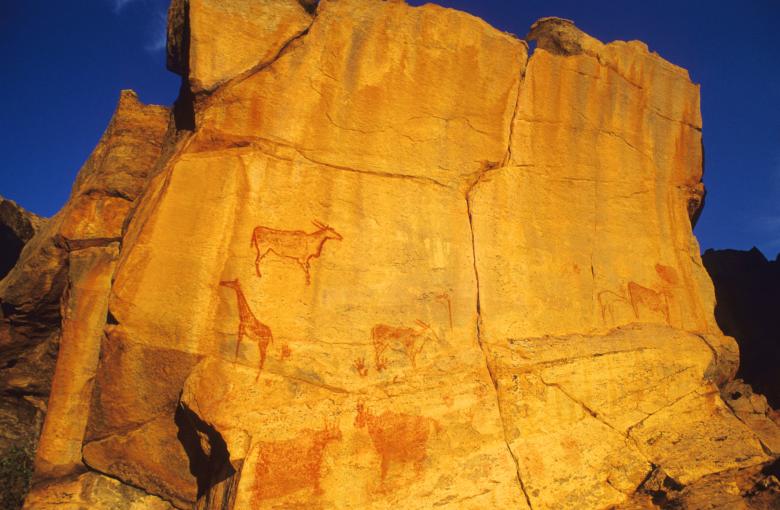

Half of Africa’s elephants live in the Kaza region , a quarter of all African wild dogs and 20 percent of all lions. From the zebra to the leopard, from the aardvark to the reed, here you can feel what barren deserts, dusty savannahs, lush green wetlands or primeval forests need. With the Victoria Falls, the rock paintings of Tsodilo and the Okavango Delta, there are also three World Heritage Sites.

Kaza is a dream for tourists. And that is why the tourists should now help that this natural space is not destroyed. And in order to protect the ecosystems, the former civil war country Angola must also be opened to tourism.

That should change. Germany has promised 3.5 million euros in development aid to clear away the mines to stop poaching in the 42,000 square kilometer area in order to protect fields with electric fences. 73 rangers try to deter poachers with quads, old rifles and two aluminum boats.

“That sounds like little, but they are important first steps,” says Paul Funston, the Lion Researcher. “Angola and the large amounts of water from the clouds that are raining over the highlands and gathering in the rivers are hugely important to many of the ecosystems of the Kaza region.”

For the neighboring countries, it is essential that this area is developed quickly and sustainably. “The governments of Angola and the world must act wisely here.”

Vacationers bring money and jobs

Tourism plays a crucial role in such wise development, he says. Because if money and jobs came to the region with guests from all over the world, then the protection for the animals and for nature would be guaranteed.

Only 40 kilometers away, the “Sasha Lodge” is about to open. The round-built cottages are located above a bend of the Cuando River, through beeches and papyrus scurry bee-eaters and kingfishers. Crocodiles, elephants, kudus and impalas can be found here.

The infrastructure is still a problem, the slopes are only for the adventurous, cell phone reception does not exist. There are also no regulated border crossings, who wants to enter from Namibia, must first contact the Angolan border police. In addition, many Angolans speak only Portuguese.

“Oh, that’s not a problem,” says Kai Collins. He is the head of Wilderness, a travel agency that combines luxury tourism with nature conservation in Africa and involves local people. In Wilderness hotels, guests get their own glass water bottle, which they can fill at any time for free – plastic is frowned upon.

The staff comes from the region, children of the surrounding villages are invited to get to know the hotel business. There are shops with locally made jewelry, carvings and recycled aluminum cans. It is involved in elephant conservation and supports the release of rhinos.

To bring tourists to Luengue-Luiana, says Collins, you just have to create a runway, the guests could first stay in the “Sasha Lodge” or in a camp on the banks of the Cuando. Between 500 and 1000 adventurous tourists are realistic within the next two years, Collins believes he has convinced himself three days ago of the tourist potential of the park itself.

Ecosystems like the Okavango Delta are in danger

Two weeks later, he sounds a bit more disillusioned by mail. He says, one has to do a market analysis and a feasibility study first. However, it is important that Angola is supported in locating ecotourism in the region.

If Angola uses tourism income to make it safe for animals as well, this could reduce the wildlife conflicts in other Kaza regions – because then elephants and lions would have more space.

For tourism managers and conservationists, there is another reason why the Luengue-Luiana National Park needs to be developed as quickly as possible. The tributaries for Zambezi and Okavango spring from the highlands of Angola, where tons of rain fall. So far, water has been flowing unhindered into neighboring countries in southern Africa. This water is vital to the heart of Kaza – the elephants in the Okavango Delta, the zebra and gnu herds of the Caprivi region, the Zambezi and the foaming Victoria Falls.

But if the plans come true to backfill agricultural water in Angola, build dams and regulate rivers, then sensitive ecosystems like the Okavango Delta will suffer. Then the tourism runs dry.

Lion researcher Paul Funston has a desire, he says, when Bruce Cockburn finishes with his melancholic song. “I want to hear lions roar in Angola .” If lions roared, he says, then there are many of them, then they would have to defend their territory. And there are many lions only when there are plenty of prey, gazelles and impalas, giraffes and zebras. When the lions roar in Angola again, the country is healthy again – ready for luxury lodges and ecotourism.